Investigating the dynamics of sound in art and our perception, alongside the silence and stillness of traditional oil painting and sculpture.

Considering looking at an art object and listening to sounds or music, “What I see is always already gone, it engraves itself into my retina as a picture of its past. The visual object is the permanence of melancholia and history. Sound by contrast is the permanence of production that uses the permanence of the monument and discards it by gliding over its form to produce its own formless shape.”

Sound consists of vibrations that travel through the air or other mediums and are heard or detected when they reach a person’s ear. Sometimes we respond to these reverberating sound waves physically as harsh sounds can make us recoil or cover our ears, affecting us in a way vision typically cannot. These sounds occur and emerge out of silence.

Silence is apparently the absence of sound. At the same time, it forms the context from which all sounds surface. In the gallery, we expect to approach works of art in silence, yet by the definition of a soundless silence, this has never actually been the case. Experiencing artworks in a church for example, might occasionally involve the distractions of mass, music or religious ceremonies unfolding. These influence the whole experience considerably.

Through rigorous critiques of several artists and their work, I hope to bring forth evidence from each discipline illustrating some main concerns surrounding our perception of art. Salomé Voegelin’s recent book ‘Listening to Noise and Silence’-2010 will feature as a significant text, from which I will set her theories against my chosen case-studies, striving towards a philosophy of perception.

Voegelin’s statement is submerged in ambiguity. Passing it amongst my tutors and peers, it is a thought that is complex and difficult to grasp. Yet grappling with this statement forges the questioning that fuels my investigation, provoking a critical response. Voegelin alludes to the idea of the visual art object, a painting or sculpture being dead and buried. Its tomb is a monument shrouded by formless, unremitting sound art. This thought however, may disregard the unique silent power of traditional painting and sculpture which occasionally can be very striking. The ways in which both visual and sonic disciplines are perceived can be very different. So as I exhume Voegelin’s visual object I shall examine the permanently produced experience of sound art against the silence and stillness of oil painting and sculpture.

Sound is a key element in my personal creative practice, as is the way in which we perceive it. My own kinetic sound sculptures seem to occupy a different area in my perception from that of paintings. This investigation peruses those differences and seeks to shed light upon the mechanics of seeing and listening. Sound is resonating throughout contemporary visual culture, affecting us all as it inevitably surrounds us. Our universe partakes in natural and rational order, constantly in motion and in a sense, musical for being so. In silence, we encounter a deep feeling, often a fear as we find the need to fill it with sentimental sounds or music.

The next three examples establish some mechanics involving sound and silence in both painting and in sound art.

Matisse’s still life painting, ‘Dishes and fruit’ - 1901, is an example of how a silent painting can be silent in subject matter also. The inanimate still life offers a depth of this silence and charges the whole image with a sense of anxiety. The image evokes a tension that concentrates the viewer to sit in silence and something is transferred from the painting to the viewer at the speed of light. The brush marks are static and still although they trace the movements of Matisse’s hand as they articulate the arrangement. From this, a remarkably tense image is generated. This is an image of silence happening in and amongst these objects. Figure 1

The barbarity, the ferocity, the horror. Guernica. The challenge of abstraction forces us to react in a confused but emotional fashion. A bold, confident and controlled brush paints forms in contrasting light and dark. But for all its intensity and drama, the image itself remains strikingly silent and still. This by contrast, is a silent painting about noise, in this case the noises of brutal massacre. This can only allow the sounds of destruction to manifest in the mind. Or the unmitigated silence is more disturbing still, generating a great sense of unease. This is the undoubted presence of absence. “First, small parties of aeroplanes threw heavy bombs and hand grenades all over the town, choosing area after area in orderly fashion,” reported George Steer of the Times, forcing thousands to take refuge underground. After the bombing, in the cellars and dugouts under the ruined town women and children were waiting in silence. Listening. Waiting until it was safe to emerge. How long would you wait? For how long would you keep listening in anxiousness to the tense and persistent pressure of silence? About twenty minutes perhaps might be long enough? “Next came fighting machines which swooped low to machine-gun those who ran in panic from dugouts, some of which had already been penetrated by 1,000lb bombs, which make a hole 25ft. deep. Many of these people were killed as they ran”. When we are engaged in listening to silence we are engaged with ourselves and this can often be quite an uncomfortable situation. Naturally we might choose to evade it.

We must remember however that this is a painting and it hangs in the Reina Sofia Museum of Modern Art. It exists in our world, which is a noisy environment full of coughing, sneezing and shuffling feet. Figure 2

When I listen to a recording of Keiji Haino’s performance at the Drake Hotel Underground in Toronto-2005, his voice enters me through my ears. He screams and howls in varying pitch. High screeching is abrasive to my hearing as is the low growling, it rumbles in his throat and mine. His intension is not to communicate or to be understood but only to exclaim. His entire body escapes through his mouth in a manor that transcends language as a primal and barbaric yawp. I heard his vocal chords oscillating in a shockingly crude and raw delivery, not unlike the jarring spectacles of Hermann Nitsch’s gruesome performances, (See Appendix). We reconnect with that which is most basic inside us. The exertion is so forceful he collapses the distance between himself the maker and myself the listener. I feel no distance at all. His voice is in my head. I am after all listening to a recording and I listen to it in the context of my room but when I close my eyes we are in the same position. We meet in the dark.

When I look at a painting, vision naturally assumes a distance between myself and the object in view. Seeing always occurs in a different position, away from the seen, however distant. A necessary space for contemplation is always present but from this distance between the viewer and the surface of the image, we may experience a detachment as we do not depend on the mind for the paintings existence. It is instantly justified and objective and we unquestioningly believe it to be true.

In contrast, when we hear sounds we are full of doubt and faced with the challenge of deciphering what we hear whilst experiencing the phenomenon of hearing it. This is very much a visceral encounter, stirring our inner most feelings. Hearing does not present a distant position or meta-position, instead we are always simultaneous with what we hear. Our bodies and minds are happening at the same time as that which is heard as we navigate through resonating sound waves.

Voegelin describes the act of seeing not only as a physiological fact but as a way of engaging with the world around her. When I see countless reproductions of Picasso’s Guernica, although modified in the context of my own environment, what I see is essentially a static image. However long I look at it, the sensation of seeing is one that captures, disciplines and orders the seen, yet that image has no duration, the sensation has been and gone. Although I am engaged with the image I am not simultaneous with it. This is not as negative as it may seem, only different, because the image in silence has a unique dignity and presence. The silence is uncanny and the stillness is remarkable.

Listening to Haino’s performance, or anything else, I experience a lasting sensation. The act of making is unfolding and it is simultaneous with my listening. I am carried through the work in time and experience a duration that could potentially go on forever. However distant I am from the source of the sound makes no difference, the sound still arrives at my ear. If I am out of earshot, I am not involved with the artwork in much the same way as being unable to view a painting or sculpture from a different room in a gallery. Listening within the changeable parameters of a sound piece’s source would suggest I am moving within an auditory object with no set frame or structure. In effect this could be like an invisible sculpture, not one that we see but one that we hear. Marcel Duchamp pioneered this thinking of sound or music being a spatial and sculptural art rather than a time based art with ‘Erratum Musical’ – 1913. (See Appendix)

Sound can have a blocking effect as we attempt to think critically about it, made so by its fleeting and temporary nature, especially against the image that remains constantly with us and appears more stable and dependable.

“Original paintings are silent and still in a sense that information never is. Even a reproduction hung on a wall is not comparable in this respect for in the original the silence and stillness permeate the actual material, the paint, in which one follows the traces of the painter’s immediate gestures.” Arguably this too has the effect of closing the distance between the artist and ourselves as our eyes move over a painting we may project the illusion of those marks being made the moment we see them. The viewer is the changing variable in visual engagement whilst the image remains the same. The subjective soul meets the objective object.

Perhaps experiencing a visual in total absence of sound or muteness is too much for us to behold. In actuality, does sound ever disappear? Our apparent anxiety within silence would suggest our response is a deep and inward one, something we all might assume. Possibly Haino’s performance is a means of exclaiming this visceral frustration, that all sound retracts back into its silence and this is his attempt to escape that fact, at least for a while.

We encounter the inanimate still life in a silent and striking aura. When a painting communicates sounds from its silent image, the experience is altered to a more grating situation where the viewer may project imaginary sounds over the unearthly silence, perhaps as a way of making the engagement whole.

John Berger suggests that original silent and still paintings pervade and spread throughout their material, so that the viewer may perceive every part clearly in an aura.

When we perceive a work of art, how much of our engagement is affected or modified by noise or distracting visuals external to the viewed image? To what extent is sound used in works of art or as works of art themselves?

Dynamic Things and Places.

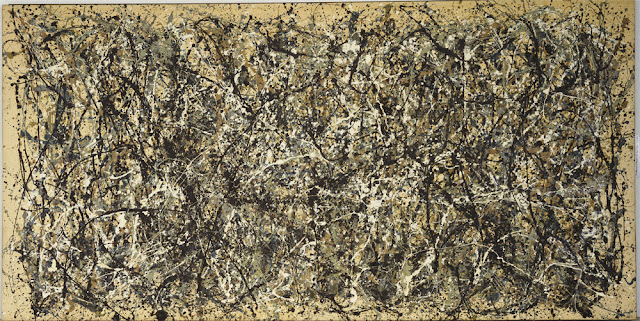

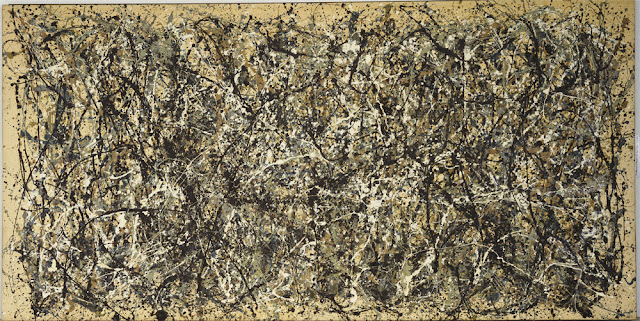

When I visit the Museum Of Modern Art in New York, I am immersed in the chaos of unorganized sounds and amongst a sumptuous buffet of visuals on the surrounding walls. I behold Jackson Pollock’s ‘One: Number 31’. Firsthand, there is no questioning the power and presence of Pollock’s paintings. What brings this image into existence is the scale as the canvas engulfs the wall. It imposes and it intimidates and it is easy to feel devoured in its energy. The unframed canvas brings a sense of vitality to the piece allowing the image to expand out from its centre. Figure 3

My eyes scoot around until they anchor in particular spots of minute details. Nimble lines of enamel paint can be detected as they whip across the raw and unprotected canvas. It becomes clear that Pollock utilizes movement in his method. The laws of gravity and physics are exploited in his technique. What I see are the remnants of a ritualistic performance and I struggle to assess which has the majority of control, the physicality of the natural world or Pollock himself. “I can control the flow of the paint, there is no accident, just as there is no beginning and no end,” Pollock claims as he strides across his laid out canvas. However, I know there was a great deal of controlled chance and ambiguity employed in his practice, thus allowing variables like viscosity and gravity to be negotiated. His gestures are recorded but indirectly, his arsenal of mark making is enhanced by his tentative strategy. De Kooning remarked; “Every so often, a painter has to destroy painting. Cézanne did it. Picasso did it with cubism. Then Pollock did it. He busted our idea of a picture all to hell. Then there could be new paintings again.” These ‘new paintings’ would involve the dynamics of chance and fling the door open to chaos.

As I sit looking at this painting, in thought about its creation, lots of things are affecting the way in which I perceive it. I see it in the more established light of an accumulated historical context of abstract expressionist paintings. Paintings by Mark Rothko from around the corner and other New York School associates support this painting in a joint rigorous intellectual pursuit where spontaneity and experimentation were commonplace. This may offer a sense of reassurance, enhancing the fact that what I am looking at resonates with authenticity as I observe its aura. Visual noise can accumulate in the form of school children or crowds.

Another visitor sits beside me and she places her handbag with a chain handle onto the bench. The gentle, brief clatter against the wood sounds and instantly the painting is modified. Aspects of the rhythmic nebular now seem more prominent in the light of this sound. The marks are now jostling together in the flux of sonic energy, wrestling forward. Then, back in silence, or the quieter noises one naturally experiences in a public gallery which too rub against the image, hindering its impact. I listen to myself churn.

Listening is not a science but rather a way of engaging wholly with experiences. It is a screening process, full of playful misconceptions and subject to idiosyncrasy. But for all its undependable tendencies listening as well as looking start to formulate the perceived into something trustworthy. Listening to silence must involve listening to one’s self in a sonic life world with tiny sounds from any context, whether it is musical, visual or anything else.

Discourse involving silence is dominated by the ideas and work of John Cage, in particular 4’33’’, a seminal work integral to twentieth-century sound art and contemporary music. Echoes of Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ -1917, are present in 4’33”, perhaps it evokes and reflects Fountain’s impact on visual art onto that of sound and music. It is closely related in concept to the readymade because through the silence we begin to question and encounter the conventions of performance and the nature of music in much the same way as Duchamp when he brought a urinal into the gallery, questioning the aesthetic content.

Cage wrote 4’33’’ as a piece in three movements where the performers remain silent. This allows the audience to listen to the sounds inside them and each individual perceives the piece in a different way. The tiniest sounds would be amplified as they are heavily focused upon and the audience was made to listen to itself. Silence is like the every day material from which a readymade could be articulated. The sense of disengagement from the artwork, present in Pollock’s drip paintings also exists here. Cage and Pollock share in a deconstructive process that obscures our social and cultural engagement with Art. Our involvement in each piece is now thrown into focus as we become an active element. It is as though Cage exploits the auditory object of the audience, these assembled spectators are listening to themselves listening.

Of course the silence of Cage’s 4’33’’ is not a sonic silence but a musical silence. His curiosity in silence resides in bringing any and every sound into a musical frame, thus making any sound, however ordinary, music. This is enhanced when music is separated from the context of the concert hall, as Pollock’s questionable and controversial technique was established in the gallery. Controversy aside, each artist produced an aesthetic moment in their work. With Pollock arguably it could have been in the process of making where he stretches and strides over his canvas, dripping enamel paint with a flailing arm, or in being encountered by the remnants of this method. Both active and passive sides are equally valid aesthetically, however their aesthetic moment is immediately thrown into the past. With Cage’s 4’33’’ members of the audience would feel carried and involved through an aesthetic moment that is much more sustained, the duration of which would last through the entire performance time.

“When there is nothing to hear, so much starts to sound. Silence is not the absence of sound but the beginning of listening.”

Sonic silence is a myth. Cage describes the time when he entered an anechoic chamber, a room designed to eliminate noise and echoes. “I entered one at Harvard University several years ago and heard two sounds, one high and one low. When I described them to the engineer in charge, he informed me that the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one was my blood in circulation.” Until we die there will always be sounds and they will continue after death. We are never mute.

Rarely is one’s perception turned inwards, pointed into one’s physical self. The audience becomes the performance. This is art in the habit of throwing the world back at us. Much like Anish Kapoor’s mirror works (See Appendix). As with Pollock, his paintings often being described as frozen visual music, are however silent in the same way as 4’33’’. The painting is indeed modified by the sounds within the proximity of my hearing, but its image is gone, the aesthetic moment has passed and the image is not simultaneous with the surrounding sounds. Perhaps this inevitable interfering sound is the music of the spheres, the planets revolving and our harmonious universe forever in motion. The painting itself exists entirely in the visual world and it is our perception of that painting that brings it into competition with the sonic world, with the baggage of our sonic sensibilities. This is of course because our bodies are equipped with both eyes and ears. Where seeing is an act of choice, listening and more specifically hearing is not. We are always sensitive to the noises and sounds within our environment. The nature of our world being so diverse requires us to have more ways of perceiving it. Being only able to see would be remarkably two dimensional, however the role of sound is not simply to flesh-out the visual.

“The understanding of oneself in silence is a pre-requisite for composition and its criticism alike. The ability to listen to yourself and to hear yourself fleshy within this audition is an aesthetic position that produces the work as aesthetic moment, continually now.” Voegelin adds the idea of ‘aesthetic position’ to the investigation and to be compositionally and critically aware of a sound piece is to realize oneself within that sound, as a biological fleshy mass. From this standpoint we can then experience the aesthetic moment, which in both sound and silence, is continually unfolding in the now.

The Breath of Empty Space.

When Robert Rauschenberg made nothing the subject of his paintings, everything then could enter in. In response to them Cage wrote, “The white paintings were airports for the lights, shadows and particles.” Figure 4a.

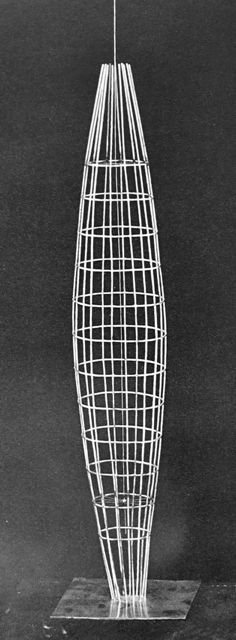

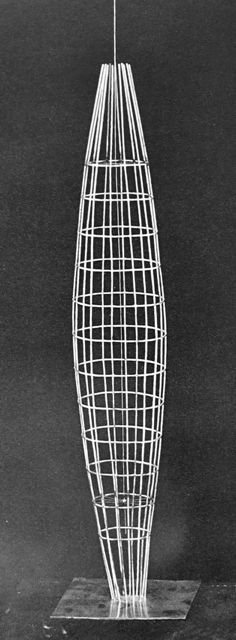

Rather than involving existentialist ideas emphasizing the artist, alone in the universe as a free and responsible agent exercising individual development, Rauschenberg instead allows the universe to pour in. The canvas is never empty but continually captures and absorbs. The viewer’s shadow may even be allowed to fall upon its surface and once more we become actively involved. “While looking at the constructions in wire by Richard Lippold, it is inevitable that one will see other things, and people too, if they happen to be there at the same time, through the network of wires. There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time.” Figure 5

In light of the aesthetic position, anything we do involves ourselves as a central anchor of experience, forever perceiving our local environments. Sound being permanently involved in our day-to-day lives can modify and obscure our perception of visuals. Many visual artists or composers arrive at sound sculpture in their studio practice and here we see a coming together of sound and the visual, whether in unity or juxtaposed.

Jean Tinguely’s sound sculptures are inhabited by oppositions. They are meticulous and casual, controlled and chaotic, they are also filled with visual and auditory stimulations. There is neither a wrestle for prominence or unison between these sensations. When I stand in front of Tinguely’s ‘Débricollage’- 1970 at Tate Liverpool, my vision captures first the three dimensional junk-collage. Second, the intermittent sounds fall in my ears as I continue to explore its vaster auditory object. This is an action happening in real time so it becomes an event. Figure 6

As I am conscious of myself within an aesthetic position and receptive to the kinetic sound sculpture, I can begin my listening. This aesthetic moment happens in the brief consecutive instants of now where my sensation encounters my perception. This concept of now is ephemeral and fleeting yet it holds a duration as I continue to listen. This is the ‘permanence of production’ to which Voegelin refers, as the aesthetic moment is continually produced whilst a listener listens.

In the unique case of kinetic sound sculpture we also experience a duration of visuals in motion alongside continual sonic stimulation. The combination of which can be mesmeric, a quality perhaps only shared by the language of film. An aesthetic moment is in fact occurring whilst looking at this piece as well as listening. Reciprocating and oscillating limbs set the fine art object in a state of visual flux as they cycle through their motions. Via a dropping hammer or a scraping saw this kinetic energy is converted into sound, the product of which is emitted from the piece as sonic material. This sonic material falls in my ears as the changeable image enters my eyes. The symbiosis of sound and visuals that exists in the Art object is now shifted via seeing and listening into my mind as aesthetic moment.

Tinguely purposely placed his work in a dynamic cultural framework where being satirical and critical in his making reflects upon our technological society. These machines have no utility other than an aesthetic one, so whilst they demonstrate a close relationship with science and engineering, they critique and mock those disciplines. Something I share in my own creative practice. Figure 7

The Harmony of the Spheres.

“Harmonic power dwells within everything which is complete by nature, and appears most clearly in the human soul and in the movements of the stars.”

When I explored Laura Belém’s ‘Temple of a Thousand Bells’ at Liverpool’s Oratory in St. James’ Cemetery -2010, I assumed the role of viewer, listener and onlooker. The bells were inanimate and thus made no sound. Nor were they ever intended to because each hand blown glass bell had no clapper. Instead the sound was played digitally through positioned loudspeakers. They narrated a tale of a lost temple of bells that sank into the sea whilst describing their beautiful sound in a coy and ungainly manor. Of course this sound occurs in the greater context of its silence, as auditory objects merge from inside the room and out. Figure 8

Disappointingly, unlike Tinguely’s ‘Débricollage’, the visual and the sound were separated initially and they would not meet in my perception. Instead the glass bells had the sound cast onto them rather than discharging their own honest tones. Yet the bells in the story never lost their sound, perhaps the piece represents our apparent inability to listen and to engage with auditory aesthetics.

“Mystical dance, which yonder starry sphere

Of planets and of fixed in all her wheels

Resembles nearest; mazes intricate,

Eccentric, intervolved, yet regular

Then most when most irregular they seem,

And in their motions harmony divine

So smooths her charming tones that God's own ear

In ancient astronomy, the universe was believed to consist of a series of spheres, all rotating around the earth. Within these spheres, the stars and the planets were embedded. In motion, the spheres would create harmonious sounds and divine music with beautiful tones. It was believed that when humanity was cast out of paradise, we lost the ability to hear this heavenly music. Like the sunken bells in the temple, they are lost and in Belém’s piece they are mute but with a separate articulation of synthetic ringing tones. In light of humanities loss, we forever strive to return to paradise through our own ways and means. Through art we may critique it. The digital sound might perhaps be a metaphor for our failing attempts to regain these beautiful sounds.

This may suggest that our universe is harmoniously and mathematically rational although appearing to be chaotic. And our creative actions within this frame in turn resonate with harmonious beauty.

To grasp an installation such as this, one may have to use the “conceptual practice of listening; to experience the installation from the depth of its complex and interweaving possibilities rather than understand its totality.” Voegelin suggests a strategy of engagement relating to sound and installation work. Without sizing-up its whole entirety one can find a path within the works many parts and corridors and through this draw out sensations of delight or aesthetic moments. This may occur in brief moments of coincidence as changeable sounds mix with appearances, as we perceive the subject. Or in a silent and still image which endures.

Listening as a ‘conceptual practice’ would suggest following a singular idea or mental method, thus allowing one to engage with different artworks with a consistency in approach and standpoint. However, interdisciplinary and sound installation works stretch this concept into something a little more challenging to follow. From experiencing Tinguely’s ‘Débricollage’, when focusing on its sound, I know there is a lot of room for playful distractions and my attention becomes diverted towards visual puns or erratic movements. All the while, I have the immersive task of juggling this interplay of sensations.

Voegelin presents listening almost as a science and I would have to disagree in this respect, given what I have experienced in the perception of artworks. Listening and looking as physiological facts alone cannot encompass the entirety of the experience, nor do they see the dynamics of its conceptual status. This is interpreted in the psyche and can be quite playful or misled. Each mind is of course an individual and so interprets individually with respective, changeable inclinations. One’s attitude towards a multitude of different artworks is never initially the same. Vision captures instantly, as I gather it does not exist within the frame of time and so the sensation of its appearance has no lasting duration. Thus the visual starts to form a foundation of our initial thoughts regarding each piece. Whilst this happens, one experiences the lasting sensation of sound emerging from the context of its silence that occurs in time, far exceeding the immediacy of the image.

“Everything that is governed by natural law partakes of some rational order with regard to its movements and the object of its movements. To the degree that this [rational order] is perceptible in its orderly rhythm, so it becomes for these phenomena their mother, nurse and healer and everywhere causes what one may call beauty.” It is unknown to me whether the celestial concert moves in total silence. Perhaps its sound is so low in pitch or far away that our ears cannot receive it. What is significant though, is the fact that we are unable to hear its music and instead we must confront the pressing silence. This idea brings to mind the clapper-less bells in Laura Belém’s sound installation.

Silence is never without sound as listening is never without the confrontation of one’s self. Cage makes an example of this in 4’33”. Listening allows the universe to pour in to our bodies. However hard we try, we can never experience being mute within a soundless world. Rauschenberg’s canvas is never empty in the same way that silence is never without sound. Instead the canvas acts as a great receptor, continually capturing and transmitting that image back onto us. This is the image of the universe as seen by the surface of the canvas, having been acted upon by shadow, light, dust, and sound.

In the brief moments that Pollock’s strands of enamel paint were falling in mid-air above the canvas they partake in the mightier activity of the cosmos. Even as that flick of paint is suspended in the air, the earth is spinning, plunging continually and this must carry some influence as to how the paint falls and lands. Even Pollock might lean against the pillars of our harmonious universe when he distances himself from his work the heavenly apparatus can intervene and make it beautiful.

Pollock’s ‘One: Number 31’ is a static image. It is remarkable for being so, as its own silence and stillness dominates and reverberates in the visual world. Its image is vibrating at the speed of light towards our perception. It is received continually yet deciphered instantaneously as we perceive it from our aesthetic position, which interprets the work as aesthetic moment. Through our perception however, we also bring to this image the auditory baggage from local surrounding sounds. These can create a friction with the image in our mind as the sounds jostle for prominence when we interpret them together.

Our stimulated perception of sensorial material originating from artworks resides within the aesthetic moment when we consider the experience to be beautiful. One must also realize ones’ own aesthetic position within this engagement.

“Vision captures, orders and disciplines space but it does not see the simultaneity of its time.” What we do bring to the situation of seeing however, is the context of our own visual histories and they allow us to plot variations of the seen image as we continue to experience it. Listening alone offers the dynamic of experiencing silent and still images in time and arguably, for this reason may compromise the contact with a painting or inanimate sculpture. Because listening happens in time, we may become more concerned with our own mortality. Humanity notices the pressure of time as we feel inclined to fill it with things we find meaningful.

I believe this is why Tinguely’s ‘Débricollage’, or the medium of kinetic sound sculpture is so significant. As our separate senses gather together the visual and sonic material that is released from the art object, our perception merges them back together and formulates them into something whole. It has a physicality that shares with us a lasting mortality. We also share an existence and happening within space and time, not only its sound but its image is occurring in both. This is why I was disappointed with Laura Belém’s sound installation ‘Temple of a Thousand Bells’, there was no re-fabrication of sensorial material in my perception. They were presented separately and interpreted separately thus I sensed the piece was un-whole and fragmented.

A philosophy of perception must involve the accumulation of sensory material in the mind that is concurrently processed and formulated into something reassuring and trustworthy. The viewer is always central in every perceptive situation as individuals, we are each sensitive to stimulations that happen against our moving bodies. Objective sensory material and energy falls upon our subjective minds via our perception.

Visual and sonic encounters are equally prominent. Yet they appear to hold very different qualities. The immediacy of the image has an instantaneous presence, experienced in a distinct atmosphere. The continual production of sound recalls a sense of an event that occurs simultaneously with our mind. There is also a sense of sound occupying space as an auditory object.

Voegelin’s book has proved a useful guide through the discourse related to listening and sound, yet it has not been unquestionable. The text has a way of formalizing perceptual encounters whilst I have given evidence through personal responses to the more playful aspects of experiences. For example Tinguely’s ‘Débricollage’ shatters any strategy of engagement forcing the viewer into a state of joyful confusion.

Reflecting upon what I have discovered, I realize to be totally conclusive at this point would be premature. This is a question that carries on beyond the points raised in this extended essay. It is in wrestling with these ideas that ignited my thinking and generated my original interest in a philosophy of perception, of which I am now pleased to be more critically informed.

Salomé Voegelin, Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards the Philosophy of Sound Art, New York, The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. 2010 p.169

2 George Steer, Bombing of Guernica: Original Times Report, 1937, [online] http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article709301.ece

George Steer, Bombing of Guernica: Original Times Report, 1937 [online] http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article709301.ece

H.R.Rookmaaker, Modern Art And The Death Of A Culture, USA, Crossway Books, 1994 p.164

John Cage, Silence, Great Britain, Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd. 2009, p.8